Michal Czinege is experimenting with natural pigments to make his own paint.

story

15.11.2023

Radically curious

Temppelikatu artist studio’s new resident Michal Czinege isn’t afraid to feel uncomfortable in order to learn new approaches to art – be it making paint with ashes, building installations with shadows or moving to a whole new country.

Starting from scratch can be be both exhilarating and exhausting. For visual artist Michal Czinege, a big turning point in his professional life was the move from Slovakia to Nurmes in North Karelia in 2016.

For many years, Czinege and his wife, Finnish artist Maija Laurinen lived in Bratislava, where they both had studied and earned their Doctorate degrees in Art. Czinege had established himself as a well-respected painter, and worked as assistant professor at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design. Now the couple inhabits an old wooden house in a town with a population just under 10 000 people.

”When we moved to Finland, things started to open up, because I lost my status and many expectations around my work,” Czinege says.

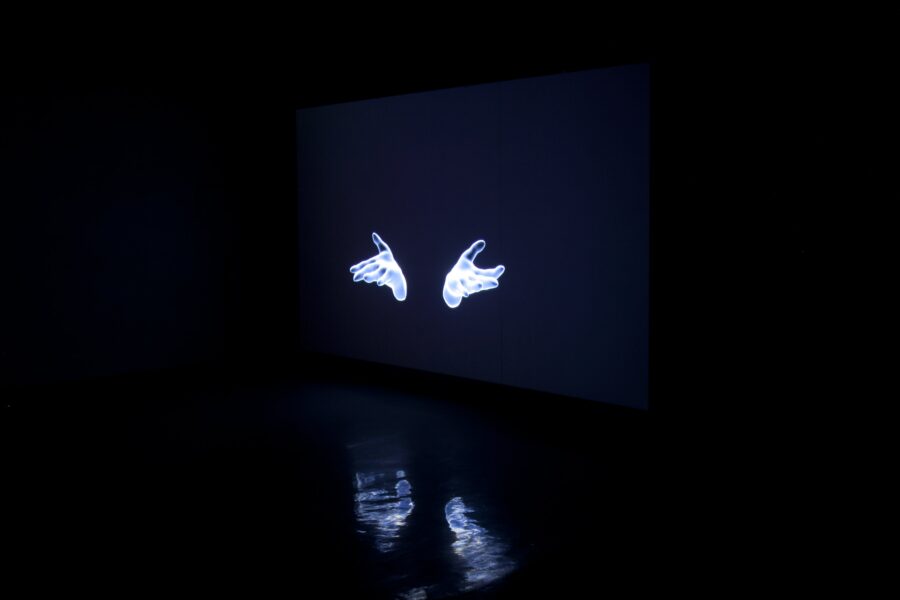

Czinege has always been interested in perception and particularly the moments before recognition – when we are not quite sure of what we are looking at, and various potential interpretations are floating in the air.

In Finland, he started to explore these themes with larger, more architectural installations, often incorporating interaction between colour, light and shadow to make details appear or disappear. Painting is still the base for his pieces, but not necessarily as a traditional flat canvas.

”

To be able to present a nice, polished artwork in a nice space, you usually have to produce a lot of trash first.

Before, Czinege says, his knowledge of the tradition and techniques of painting sometimes made him overly self-critical, limiting new experiments. Venturing into different media without much pre-existing knowledge on them has removed many limitations.

”It is funny how you can feel like a prisoner in your own mind. And taking just a few steps into a different direction makes you feel completely free,” Czinege muses.

But trying something new has also meant countless hours of watching tutorials, trying to overcome tehnical issues and making mistakes. This is particularly true in Nurmes, where there isn’t much of a creative community around to rely on. Czinege and Laurinen, who both work on their own projects but also collaborate occasionally, have needed to learn to realise most parts of their work without any help.

Luckily Czinege is someone who, according to his own words, doesn’t mind taking the time to figure things out.

Cabbage, eggshells and lupines

Moving to the Finnish countryside has also made Czinege profoundly reconsider the sustainability of his artistic practice.

”The problem is that I like doing big installations, and the bigger the pieces are, the more material is consumed. To be able to present a nice, polished artwork in a nice space, you usually have to produce a lot of trash first,” he says.

At some point, Czinege was seriously considering giving up painting altogether, as doing it using non-toxic materials felt almoust impossible. Now, he is experimenting with natural pigments to make his own paint. So far, Czinege has been using things such as cabbage, eggshells, blueberries – and lupines, ever since he discovered the plant is considered an invasive species in Finland.

Making one’s own paint means working at a much slower pace than what he was used to before.

The artist has recently finished a large installation that will be exhibited in Slovakia. In the piece, entitled Garden of Death, painted silhouettes of extinct plants from the North Karelia appear on canvases as momentary bursts. Impermanence is also present on a material level – the paint used is made with ash from firewood burned in Czinege’s oven.

The artist residency in Finland allows Czinege to continue experimenting with ecologically sustainable materials and colours.

”I then really needed to think about how others observe and interact with my installations. This was new to me, and very interesting,” he recalls.

”I found the ash had the exact colour I needed to work with the wavelength of the light I wanted. But it did take a couple of weeks to just to get the colours.”

New encounters with the audience

Visual art always carries certain images or symbols for the viewer to interpret, but Czinege’s spatial and site-specific work often relies on audience’s physical presence in the space more than traditional paintings.

Often Czinege has witnessed confusion, as people have not quite known how to interact with his installations. The artist recalls an exhibition in Gallery Lapinlahti, where he showcased a piece with the idea that people could go between a spotlight and a black canvas, creating different shadows. But at first, most people just stood further away, waiting for a projection to start.

Some of Czinege’s recent art only fully exists as encounters between the viewer and the work. But he is also interested in a form usually considered quite permanent: the book. Since the beginning of his career, Czinege has created artist books to document and reflect on his working processes.

For Czinege, making a book means approaching materiality differently than in his work otherwise, and he has also showcased artist books as part of exhibitions. In his experience, a book seems to remove a lot of the distance between the art and the viewer.

”Perhaps it is because you can touch books, flip through them and fold them if you wish. But people are always much braver to ask questions about my work when they are looking at my books.”

Michal Czinege has always been interested in the relationship between our perception and reality.

Radical attempt at sustainable art

Starting from October 2023, Czinege is temporarily back to being a city-dweller. He spends six months living and working in Helsinki at Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation’s Temppelikatu artist studio. For one, this allows time and space for creating new artistic connections and collaborations he has longed for.

Reciprocally, Czinege would also want to invite more artists to visit Nurmes and the studio space he and Laurinen rent in an old bank building in town. The couple have even turned one corner of it into a small exhibition space, aptly named ”Koppi”.

During his artist residence, Czinege plans to continue exploring materials and colours that burden the environment as little as possible. In an urban environment, this could mean using leftovers from flower shops or from his own dinner ingredients, for example.

”We will see how radical I will get”, Czinege says and laughs.

”I guess I am a person who often does things in a complicated way – not because I like it, but because it feels important. And I do think that often looking for a more sustainable approach to things simply means enduring more troubles and inconveniences.”

Text: Heini Huhtinen

Photos: Miikka Pirinen

Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation’s artist studio offers Finnish visual artists or visual artists living permanently in Finland the opportunity to live and work in Helsinki. The studio is intended for visual artists living outside the metropolitan area for working and living for 6–12 months.